I had yet not quite passed the bounds of youth and reached early manhood when I knew of your name and your reputation, not yet for religion but for your virtuous and praiseworthy studies. [...] you have surpassed all women in carrying out your purpose. - Peter the Venerable, Abbot of Cluny, in a letter to Héloïse dated 1142.

I had yet not quite passed the bounds of youth and reached early manhood when I knew of your name and your reputation, not yet for religion but for your virtuous and praiseworthy studies. [...] you have surpassed all women in carrying out your purpose. - Peter the Venerable, Abbot of Cluny, in a letter to Héloïse dated 1142.

Readers of Quirkality will be familar with the lives of Pierre Abelard and Héloïse d'Argenteuil. In this second part of their story, we look more closely at the conflict between Abelard's dualistic philosophy of love and, we claim, Héloïse's more rounded, human philosophy.

After the unhappy events which saw Abelard castrated and Héloïse sent, by Abelard, to the convent where she had received her education, Héloïse took the veil at Argenteuil. She had no desire for it, indeed the idea was hateful to her; it was at Abelard's bidding that she did so:

[...] I have carried out all your orders so implicitly that when I was powerless to oppose you in anything, I found strength at your command to destroy myself. ... I changed my clothing along with my mind, in order to prove you the sole possessor of my body and my will alike.

Héloïse and her community were evicted from Argenteuil, and in 1129 Abelard and Héloïse founded the Order of the Paraclete. It was here that Héloïse came by chance across Abelard's Historia calamitatum. Héloïse was hurt and angered by what she read. How could this man, her Abelard, claim that their love was earthly, carnal, and nothing more? The philosophy of love which Abelard sets out in his "letter to a friend", his Historia calamitatum, is dualistic: he conceives of a divide between body and mind, passion and reason. For Abelard, love begins and ends with the body. He had "yielded to the lusts of the flesh"; seduced Héloïse for his own ends.

Upon reading these words Héloïse was not only angry, but confused. It is easy to see why. In letters discovered by a young monk in Clairvaux in 1471, a writer identified only as V (from Vir, for man) writes:

Love is ... a particular force of the soul, existing not only for itself nor content by itself, but always pouring itself into another with a certain hunger and desire, wanting to become one with the other, so that from two diverse wills one is produced without a difference...

To his correspondent, M (from Mulier, for woman), he goes on to claim that:

[...] although love may be a universal thing, it has nevertheless been condensed into so confined a place that I would boldly assert that it reigns in us alone - that is, it has made its very home in me and you. For the two of us have a love that is pure, nurtured, and sincere, since nothing is sweet or carefree for the other unless it has mutual benefit. We say yes equally, we say no equally, we feel the same about everything.

These letters, between V and M, have been identified as the lost love letters of Abelard and Héloïse. In his Historia calamitatum Abelard speaks consistently of earthly, physical passion, yet it is clear from what he writes in the lost letters that he loved Héloïse wholly and intensely. These words belie his claim that love is merely physical; these are not words of bare seduction.

Héloïse does not accept Abelard's position. For her, love is not limited to the body. Her love for Abelard persists because her mind "is on fire with its old desires"; she cannot conceive of a love that begins and ends with the body as love encompasses the whole person.

Héloïse demands that Abelard love her mind and soul even though he can no longer love her body, as he has been castrated:

While I am denied your presence, give me at least through your words - of which you have enough and to spare - some sweet semblance of yourself.

In Héloïse's beautiful and profound philosophy, "love does not easily forsake those whom it has once stung." In a complex web of interactions, responsibilities, desires and mutual pleasures, "the services of true love are properly fulfilled only when they are continually owed." Not for Héloïse the reduction of love to carnal appetites. Rather, she provides a full and rich philosophy of love which finds full expression in her humanism.

By the fourteenth-century Héloïse's identity as a philosopher and scholar was becoming lost to romanticism and an image of her as the ideal lover. In his copy of the manuscript of the letters, Petrarch wrote "you are acting throughout with gentleness and perfect sweetness, Héloïse". This picture of Héloïse, as the idealised, passive lover, persisted for centuries. The time for Héloïse to be recognised as love's true philosopher is overdue.

(Sources: The Lost Love Letters of Héloïse and Abelard, Constant Mews; The Letters of Abelard and Héloïse, trans. Betty Radice; Women in Western Intellectual Culture, 600-1500, Patricia Ranft.)

The year 1848 was decidedly nervewracking for the established rulers of Europe. Not only had Marx and Engels published their Communist Manifesto at the year's beginning, calling on the proletariat to rise up and throw off their chains, but bourgeois-democratic and progressive forces were out on the streets of European capitals, demanding the overthrow of the old quasi-feudal order. Before the year was out, France, Italy, Denmark, Germany, the Austrian Empire and the Netherlands had seen popular uprisings, the monarchies in France and Denmark had fallen, and serfdom had been abolished in Austria and Hungary.

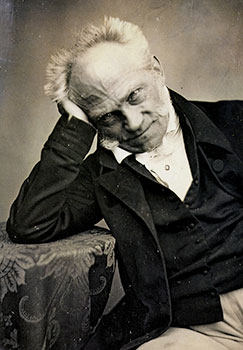

The year 1848 was decidedly nervewracking for the established rulers of Europe. Not only had Marx and Engels published their Communist Manifesto at the year's beginning, calling on the proletariat to rise up and throw off their chains, but bourgeois-democratic and progressive forces were out on the streets of European capitals, demanding the overthrow of the old quasi-feudal order. Before the year was out, France, Italy, Denmark, Germany, the Austrian Empire and the Netherlands had seen popular uprisings, the monarchies in France and Denmark had fallen, and serfdom had been abolished in Austria and Hungary. Arthur Schopenhauer, philosopher and curmudgeon, was not spectacularly successful in affairs of the heart. It is true that aged 31 he fell in love with a nineteen year old opera singer, Caroline Richter, and pursued a relationship with her for several years, but this fell apart after he refused to marry her, complaining that "Marrying means to grasp blindfolded into a sack hoping to find an eel amongst an assembly of snakes." Some ten years later, he did manage to proposition a seventeen year old girl, Flora Weiss, at a party, apparently while brandishing a bunch of grapes, but she rejected him, and his grapes, remarking in her diary that she didn't want the fruit, because "old man Schopenhauer had touched them."

Arthur Schopenhauer, philosopher and curmudgeon, was not spectacularly successful in affairs of the heart. It is true that aged 31 he fell in love with a nineteen year old opera singer, Caroline Richter, and pursued a relationship with her for several years, but this fell apart after he refused to marry her, complaining that "Marrying means to grasp blindfolded into a sack hoping to find an eel amongst an assembly of snakes." Some ten years later, he did manage to proposition a seventeen year old girl, Flora Weiss, at a party, apparently while brandishing a bunch of grapes, but she rejected him, and his grapes, remarking in her diary that she didn't want the fruit, because "old man Schopenhauer had touched them."